Focus on the Material World

by John Malloy

This is part four of a six-part series of articles. The rest of the series is coming soon....

“The more I study nature, the more I stand amazed at the work of the Creator. Science brings men nearer to God”

Louis Pasteur

The alleged entity known as “god” has no place in any scientific equations, has never been detected, cannot be used to predict any events and there is no model of the universe where its presence is useful, required, productive, or desired.

Richard Dawkins

The material world is what we see, touch, smell, and taste. From the joy of a beautiful sunset to the physical discomfort of sickness, the material world affects us every day. We spend our lives in work to obtain physical necessities for sustenance and comfort and spend our free time engaged in physical activities. Therefore, it should not be surprising that most people focus on the material world almost exclusively.

In the classical Greek and Roman world, most people believed in “gods”. The early Greek philosophers attempted to explain events around them as the result of natural processes, yet most remained polytheists. By the third century BC, Epicureanism had emerged teaching that life was governed by the laws of chance without divine intervention and denying the existence of an afterlife. Their view was consistent with the Greek attempts to explain the world in purely natural terms, yet most did not deny the existence of supernatural deities.

Some Eastern religions went in a different direction. They did not teach that there is a supreme supernatural being (i.e. god) but embraced the supernatural. These religions include the Jainism, Buddhism and some schools of Hinduism (the Samkhya School). They had concepts of the non-material, things that cannot be touched or measured, that were central to their beliefs.

Judaism and Christianity embraced both the supernatural and the natural world. A God created all of the natural world, which is maintained in part, by continuation of natural processes. Yet both taught that man must be aware of both the natural and the supernatural. Christianity especially, taught its followers that physical death was temporary and preparation for resurrection and judgement should be the primary focus of man.

European viewpoints changed in 18th century Europe. Most dramatically, the French Revolution openly replaced Catholicism with secular symbols. Monasteries, convents, and church properties were seized, and the “Cult of Reason” became the belief of the state for a short time before being replaced by Robespierre’s “Cult of the Supreme Being.” It was a rejection of the supernatural and of a supreme deity and, even though it lasted only a year, it encouraged atheistic thought in Europe in the early 19th century. This shows up in the economic theories of Karl Marx (1818-1883) and in the concerns by Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900) about the inevitable collapse of the Christian belief system and the rise of nihilism.

The world of science (or natural philosophy as it was called before the mid-19th century) was impacted as well. Science distinguished itself from religion in that it was solely concerned with the natural world. Its theories did not apply to the supernatural or non-natural forces and, as a result, it tended to discount the supernatural.

“Naturalists draw a distinction between methodological naturalism, an epistemological principle that limits scientific inquiry to natural entities and laws, and ontological or philosophical naturalism, a metaphysical principle that rejects the supernatural (Forrest 2000). Since methodological naturalism is concerned with the practice of science (in particular, with the kinds of entities and processes that are invoked), it does not make any statements about whether or not supernatural entities exist. They might exist, but lie outside of the scope of scientific investigation. Some authors (e.g., Rosenberg 2014) hold that taking the results of science seriously entails negative answers to such persistent questions as free will or moral knowledge. However, these stronger conclusions are controversial. …

Natural philosophers, such as Isaac Newton, Johannes Kepler, Robert Hooke, and Robert Boyle, sometimes appealed to supernatural agents in their natural philosophy (which we now call “science”). Still, overall there was a tendency to favor naturalistic explanations in natural philosophy. This preference for naturalistic causes may have been encouraged by past successes of naturalistic explanations, leading authors such as Paul Draper (2005) to argue that the success of methodological naturalism could be evidence for ontological naturalism. Explicit methodological naturalism arose in the nineteenth century with the X-club, a lobby group for the professionalization of science founded in 1864 by Thomas Huxley and friends, which aimed to promote a science that would be free from religious dogmas. The X-club may have been in part motivated by the desire to remove competition by amateur-clergymen scientists in the field of science, and thus to open up the field to full-time professionals (Garwood 2008)”. [1]

Science’s exclusive focus on natural phenomena has been very successful in increasing our understanding of the natural world and improving the living conditions of mankind. This has encouraged to scientific profession to become explicitly atheistic.

In an article by Lawrence M. Krauss, director of the Origins Project at Arizona State University, he wrote:

“My practice as a scientist is atheistic,” the biologist J.B.S. Haldane wrote, in 1934. “That is to say, when I set up an experiment, I assume that no god, angel, or devil is going to interfere with its course and this assumption has been justified by such success as I have achieved in my professional career.” It’s ironic, really, that so many people are fixated on the relationship between science and religion: basically, there isn’t one. In my more than thirty years as a practicing physicist, I have never heard the word “God” mentioned in a scientific meeting. Belief or nonbelief in God is irrelevant to our understanding of the workings of nature—just as it’s irrelevant to the question of whether or not citizens are obligated to follow the law[2].

Jerry Coyne, author of Faith vs. Fact: Why Science and Religion Are Incompatible when interviewed takes this even further.

One of the meanings of superstition in the Oxford English dictionary is a belief that is unfounded or irrational. Since I see all religious belief as unfounded and irrational, I consider religion to be superstition. It’s certainly the most widespread form of superstition because the vast majority of people on Earth are believers. Other forms of superstition, like astrology, belief in UFOs or telekinesis, are nowhere near as widespread. And the damage that religion has done to humanity is far more than the damage that astrology or the belief in Bigfoot has done. This is the problem with ISIS and other Islamist organizations. It used to be the problem with Christianity, as well. People get killed because they don’t share your beliefs.[3]

Strengths and Weakness of Science

The belief that a study of the natural world should only rely on observed natural processes is, at its heart, an assumption. Yet it is fundamental to the scientific process because, to date, the supernatural inherently cannot be observed and measured in the laboratory and evidence cannot be found in observations in the natural world. This has led many to conclude that it does not exist, again an assumption. The primary argument in its favor is that science has been successful in understanding the natural world without relying on the supernatural. This statement is problematical however.

In the 21st century, we live in a world that is built on science, yet it is widely misunderstood. This is illustrated by those who point fingers at those with different beliefs and charge their opponents with “denying science.” The Merriam-Webster online dictionary refers to science as:

- :the state of knowing : knowledge as distinguished from ignorance or misunderstanding

- : a department of systematized knowledge as an object of study the science of theology

- : something (such as a sport or technique) that may be studied or learned like systematized knowledge have it down to a science

- : knowledge or a system of knowledge covering general truths or the operation of general laws especially as obtained and tested through scientific method

- : such knowledge or such a system of knowledge concerned with the physical world and its phenomena : natural science

6. : a system or method reconciling practical ends with scientific laws cooking is both a science and an art. [4]

These definitions allow many different things to be referred to as science, yet definition four is the key to understanding the field. It is systematic knowledge obtained and tested by what is referred to as the scientific method. This method seeks to objectively explain events of nature in a reproducible way. It is typically divided into four steps:

- Formulate a hypothesis that can be falsifiable,

- Collect data related to the hypothesis,

- Organize the data, analyze, and compare to results predicted by the hypothesis, and

- Use the comparison to conclude if the hypothesis is correct, partially correct, or if other explanations are needed.

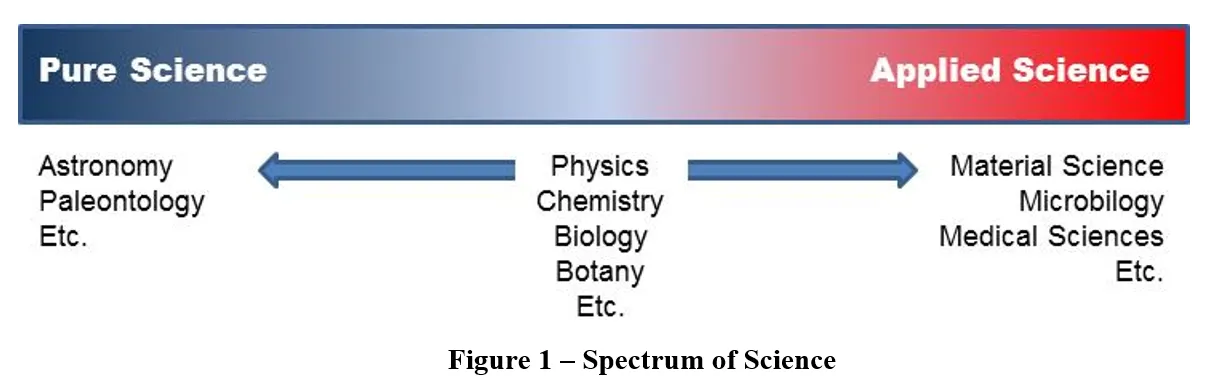

The ability of science to accurately expand human knowledge is dependent on the ability to collect accurate data and the degree that the hypothesis can be falsifiable. This makes some areas of science inherently more difficult. This is strongly related to what I call the spectrum of science. This is illustrated in Figure 1. Some disciplines, such as material science, are tied to tangible results and are essentially a form of engineering. To be useful, the material scientist must be able deliver repeatable results, even if the hypothesis he uses are not elegant or complete. Often experimental data will be used to predict results without a workable understanding of the underlying process. This emphasizes large numbers of repeatable laboratory tests, development of falsifiable hypothesis, and the consideration of alternative hypothesis, even when the selected hypothesis appears to work. Some scientific fields cover most of the spectrum with many different specialties. In these fields, as the knowledge base increases, the field transitions from pure science to engineering. One example is the work in the early 20th century of Rutherford, Soddy, and Chadwick to understand radiation and nuclear transformations, and the nature of the neutron. Fermi, Szilard, and others used this information to build a practical understanding of neutron interactions with other elements leading to the development of nuclear weapons and nuclear power. A slightly different example is the development of early antibiotics. Alexander Fleming’s research into the characteristics of Staphylococcus bacteria lead to the accidental discover that mold (penicillium notatum) killed the bacteria allowed others (his assistants Craddock and Ridley) to develop the first effective antibiotic. Both examples show how powerfully science can impact everyday life in positive or negative ways.

Some areas of science are not firmly tied to medicine or technology. Astronomy and paleontology are but two examples. While important in the characterization and classification of the natural world around us, the nature of the activity make it more difficult to develop falsifiable hypothesis and accurately test them in a laboratory. These scientific fields primarily utilize observations of nature to confirm or deny hypotheses. Unfortunately, the confirmation of hypothesis often depends upon assumptions in the interpretation of observed data. The situation is made more problematic because peer review publications are used to judge the proof of the hypothesis. This increases the role of confirmation bias and politics in the field with grant money often being rewarded in the basis of conformity with established views.

This led one writer suggest in hyperbole:

“Science really doesn't exist. Scientific beliefs are either proved wrong, or else they quickly become engineering. Everything else is untested speculation.” [5]

Science’s defenders point to the amazing transformations in our world due to science. What is often left out of this argument is that those transformations are largely due to either scientific studies that were quickly reduced to engineering or to research in the applied sciences that have a much closer tie with measurable data.

Problems with Scientific Theories about the Origin of the Natural World

As described above, our lives have been shaped, largely for the better, by advances in applied sciences. These fields are typically agnostic; they do not agree or disagree with the existence of supernatural forces. Most of the uncertainty about the supernatural and the existence of God comes from the “pure” sciences.

Natural Selection

In the general population’s mind, no one is tied more explicitly to the concept of natural selection or evolution than Charles Darwin. When he left England on the HMS Beagle on December 27, 1831, he had already studied Herschel’s book “Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy” which emphasized natural philosophy as understanding nature’s laws through observation and inductive reasoning. He had also studied geology under Sedgwick and was familiar with Charles Lyell’s works arguing that geology could be understood as the result of small processes over very long periods of time (Uniformitarianism). Lyell had just published his “Principles of Geology” attempting to explain the changes in the Earth’s surface solely as the product of processes currently visible.

The HMS Beagle visited a number of ports in South America, Australia, and Africa on its five-year, round the world voyage, but the key stops for Darwin were in the Patagonia and the Galapagos Islands. He studied major fossil finds and observed differentiation of animals in isolated locations such as the Galapagos. This led to his view that living things changed, over multiple generations, due to changing environment. He continued to develop his ideas and ultimate published them in his most famous work “On the Origin of Species” in November 1859. He stated in its introduction:

“As many more individuals of each species are born than can possibly survive; and as, consequently, there is a frequently recurring struggle for existence, it follows that any being, if it vary however slightly in any manner profitable to itself, under the complex and sometimes varying conditions of life, will have a better chance of surviving, and thus be naturally selected. From the strong principle of inheritance, any selected variety will tend to propagate its new and modified form.”[6]

At the end of the book, he concluded:

“There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.” [7]

Darwin’s theories challenged many who believed that species were immutable, but he had compiled a significant amount of data to support the theory. His observations, combined with the very long geological time periods argued by Lyell and others, gave naturalists a set of fundamental processes that could be used to explain the natural world. In subsequent works such as “Decent of Man and Selection in Relation to Sex”, he argued that humans are animals and subject to the same natural laws. During his life, he became increasing critical of the Bible as history and of religion in general because of both perceived evils and because natural selection in his mind, eliminated the need for design.

Darwin identified a process where living things in the wild, can change over multiple generations based on changes in the environment. In hindsight, this should not be especially controversial because of human experience in breeding plants and animals. There, changes in the environment are replaced by deliberate breeding programs resulting in substantial changes to the plant or animal. These observed changes have limits, however. Dog varieties can change due to environmental conditions or due selective breeding to produce Great Danes and miniature poodles, but deliberate efforts never produced goats from dogs. In the natural world, this process is sometimes labeled as “the special theory of evolution” [8]

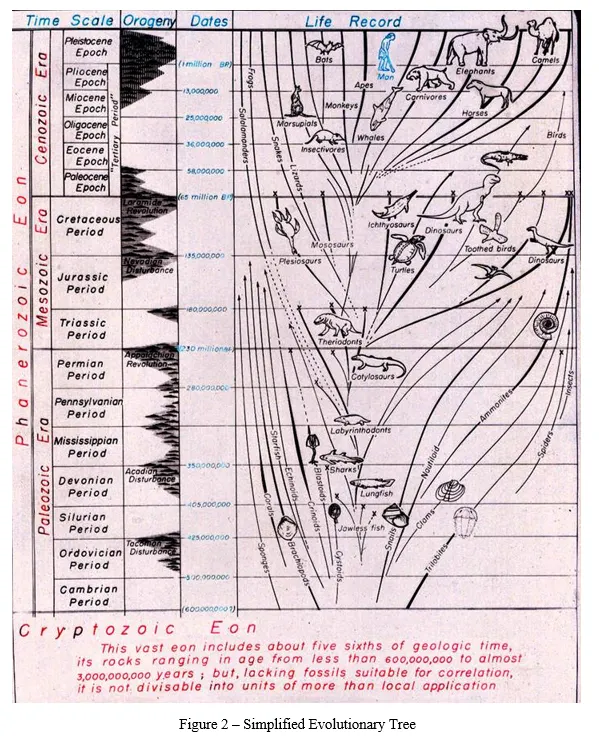

Darwin and many others came to believe that the evolutionary process could explain more than limited variations with groups of living things. Supported by the acceptance of Uniformitarianism, they believed that there was sufficient time for the development of all modern life from a primitive ancestor (Figure 2). This can be referred to as the General Theory of Evolution. [9] Because of the vast time scales involved, this is much more difficult to prove. Therefore, scientists looked to the field of paleontology to provide that proof. As one text book describes:

“The history of life ceases to be hypothesis and inference and becomes direct knowledge when fossils are available.” [10]

Yet the fossil record is not as complete as modern text books imply.

Paleontologist and Evolutionist Dr. Niles Eldedge of the American Museum of Natural History pointed out:“I admit that an awful lot of that (fantasy) has gotten into the text books as though it were true. For instance, the most famous example still on exhibit downstairs [American Muesum of Natural History] is the exhibit on horse evolution prepared perhaps fifty years ago. That has been presented as literal truth in textbook after textbook. Now, I think that that is lamentable, particularly because the people who propose these kinds of stories themselves may be aware of the speculative nature of some of the stuff. But by the time it filters down to the textbooks, we’ve got science as truth and we’ve got a problem”. [11]

Steven Gould, a well-known American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science also pointed out:

“The extreme rarity of transitional forms in the fossil record persists as the trade secret of paleontology. The evolutionary trees that adorn our textbooks have data only at the tips and nodes of their branches; the rest is interference, however reasonable, not the evidence of fossils.”[12]

These men did not make these statements because they were arguing against General Evolution. Instead, they were concerned about an inherent process in science that hides the uncertainties and ambiguities.

Many within the field point out that the lack of “transition fossils” is due to an incorrect understanding of evolutionary relationships and the focus, by critics, on artificial groups. [13]. Yet, another key characteristic of the fossil record is not as simple as the text books would display. A major assumption behind modern paleontology is that older, simpler life forms are found in oldest rock. Geologists know, however that there are no sites with compete strata from Pre-Cambrian through modern ages. Often, where multiple strata can be identified, the fossil record does not conform to the simplistic model of early life forms being found near the bottom of the geologic formation. Geologists have developed elaborate theories to how movement of the earth can leave distinct layers with patterns that do not match accepted geological time scales. Ultimately, this has led to the rejection of Lyell’s uniformitarianism, and the willingness to accept cataclysms as a key part of geology theory. Super volcanos and asteroid impacts are critical to their understanding of the natural world. This is ironic, because the very slow, gradual changes postulated by uniformitarianism were critical to Darwin’s development of his theories of natural selection.

This does not mean that there is some elaborate scientific conspiracy designed to fool us. General evolution is currently the only purely natural explanation for the existence of life. Geologists therefore interpret their data based on that explanation. If it creates complications the interpretation of strata, then there must be other processes that rearrange the strata. In many of the sciences, General Evolution must be a fact. If it isn’t, they have no conceptual approach to interpret their data. But this creates a circular path of reasoning between geologists who use fossil remains to date strata and paleontologists who are argue that the fossil record shows simple life forms developing first. Of course, neither group assumes that supernatural events ever occurred that could change the data.

Age of the Universe

One of the most beautiful natural sights is the starry sky on a clear night. Thousands of stars can often be seen with the naked eye if the viewing conditions are right. With a simple telescope, even more can be seen, including more distant galaxies. One of the early challenges for astronomers was measuring the distance between the planets and stars. As their instruments improved, they were able to measure the distance to the closest stars by measuring the difference in viewing angle when the Earth is at opposite positions of its orbit around the sun, using a technique like that used by terrestrial surveyors. The common unit of measurement, a parsec, is the distance at which the mean radius of the earth’s orbit subtends an angle of one second of arc is 3.09 x 1013 Km or approximately 3.26 light years. The accuracy of modern instruments allows direct measurements of objects up to approximately 100 parsecs (326 light years) away. But it appears that the bulk of the universe is much further away.

Edwin Hubble, in observing nebulae, concluded that many were actually galaxies beyond our own galaxy the “Milky Way”. He observed that apparent brightness which could indicate distance correlated with measured red shift of the light coming from the objects. His observations in 1929 (along with Georges Lemaitre’s a couple of years earlier) suggested that the universe was expanding and that objects with the greatest Doppler shift were travelling the fastest and were also the greatest distance away. This served as the basis for the 1958 observations by Allan Sandage to estimate the value of the “Hubble Constant” that is generally accepted today. Using this constant, it is estimated that the oldest known star is approximately 14.5 billion years old. These observations and the discovery of the microwave cosmic background radiation led many to conclude that the universe was expanding from an original explosive creation popularized as the “Big Bang.” The vast distances (~93 billion light-years [14]), and the finite speed of light suggest that universe is orders of magnitude older than any understanding of the Bible’s Genesis account.

As with natural selection, the scientists build upon existing theories and evaluate current observations based of their fit within theoretical assumptions. Critical assumptions include:

· Observed Doppler shift is due solely to velocity rather than alternative space-time interactions and correctly indicates distance,

· Background microwave emissions are due to a very energetic primordial event,

· Physical parameters measured in our solar system remain largely unchanged except where they can’t be the same (e.g. inflating universe at superluminal velocities, matter/antimatter ratios, etc.), and

· No supernatural actions affect the universe as observed.Again, this does not mean that the physicists and astronomers are either stupid or dishonest. Once the fundamental assumption is made that everything can be explained by observed natural phenomena (really the only option that the modern scientist is allowed to make), then the intellectual process is locked on a fixed path. Like the theory of General Evolution, additional observations complicate the model. Assumptions about dark matter and dark energy, inflating universe, and perhaps the most amazing of all, a single creation point in time and space whose characteristics require processes that cannot be observed today are examples. In a few ways, it is like the Ptolemaic view of the solar system (sun and planets revolve around the Earth), which grew increasingly complex with its epicycles as better observations were made and the basic model was modified to account for the observations.

Science is based on the presumption of absolute truths and seeks to understand those truths. Almost any scientist will also admit that our common understanding of the universe is very limited and subject to revision as more data is collected. Yet, like any other field, science is often driven by hidden assumptions, prejudices, political values, and selfish considerations. The desire for fame, fortune, and bragging rights exists in all fields because its practitioners are human and subject to human faults. Yet, even the most objective scientist is a captive of his assumptions and paradigms.

Can a better model be made assuming a supernatural creation? That is difficult for science to answer because there is no mechanism to encourage researchers to examine supernatural. As described above, modern science is focused exclusively on investigations assuming only natural phenomena. Research and publications based on potential supernatural phenomena would never be funded and researchers would be laughed out of conferences. Yet in their search for data to prove theories or to create new ones they, as a group, ignore another source of data. That source is human observation recorded in history. We will examine that next.

[1] Marx, K.: “A Contribution to the Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right”; Collected Works, Vol 3, New York

[2]“Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy” – Religion and Science; Jan 17. 2017; https//plato.stanford.edu/entries/religion-science

[3] Lawrence Krauss; “All Scientists Should be Militant Atheists” , The New Yorker; Sept 8, 2015

[5] Hogan James; “Kicking the Sacred Cow”; Baen Books, 2004

[6] Darwin, Charles; “On the Origin of Species”; 1859

[7] ibid

[8] Kerkut, G.A.; “Implications of Evolution”; 1960

[9] ibid

[10] Simpson G.G and Beck, W.S.; “Life” Harcourt, Brace & World, New York; 1965

[11] Niles Eldredge in Luther D. Sunderland, “Darwin’s Enigma: Fossils and Other Problems” 4th edition; Master Books, Santee CA; 1988

[12] https://ncse.com/book/export/html/1764

[13] Niles Eldredge in Luther D. Sunderland, “Darwin’s Enigma: Fossils and Other Problems” 4th edition; Master Books, Santee CA; 1988

[14] Bars, I and Terning J; “Extra Dimensions in Space and Time” Springer Science+Business Media; New York; 2010; P27